Борис Шапиро

Почему мне не нравится памятник жертвам холокоста в Берлине?

Metarepresentations and Paradigms, Ur-version

WTK - Wissenschaft - Technologie - Kultur e. V. WTK

Experience in Technology Transfer from the CIS Countries to Germany

|

Metarepresentations and Paradigms1, Ur-version |

|

BORIS SCHAPIRO |

|

Introduction |

|

The Bremen workshop “Meta-representation and (Self-) Consciousness” of 27.–29. September 2006 was looking inter alia for the “place of metarepresentation in semiotic evolution”. |

|

Historically, there are two fundamental ways to arrive at empirical basics: the analytical (Descartes, 1997) and the constructivist (Lorenzen, 2000). Our paradigmatic approach to the concept of meta-representation is based on the constructivism of Hugo Dingler’s “Protophysics” (Dingler, 1911) and his followers Paul Lorenzen, Peter Janich, and others. |

|

The difference between the paradigmatic approach and the classical constructivism is: |

|

1 The paradigmatic approach uses as basics not only the geometrical and metrological structures, but constructs the most general forms of qualities, features, feature-complexes, feature-spaces, processes, relationships, mappings, attractors, self-organizing entities as both structures and processes in abstract feature-spaces. 2 The paradigmatic approach uses as basics not only concepts valid only in the boundaries of logic, but also paradigms which are strong and non-trivial generalizations of concepts and allow consistent and rational operational activities both within and outside logical restrictions. In general, paradigms generate both concepts and paradigms. |

|

During the Bremen workshop it became clear that most scientists understand meta-representation as a self-referential dealing with items, e.g. following Wolfgang Wildgen “Images representing images, language about language and language-use, thoughts about thoughts” (Wildgen, 2006). In this sense, it |

|

This text is a short version. The full version: B.Schapiro, H.Schapiro, 2007. |

|

should be asked whether consciousness, (self-consciousness), art, ideology, science, culture, etc. are also meta-representations. |

|

In our opinion, the concept of meta-representation is necessary but insufficient for understanding consciousness, (self-consciousness), language, art, ideology, science, culture, etc. We consider paradigms potentially sufficient behavioral instruments for this purpose. |

|

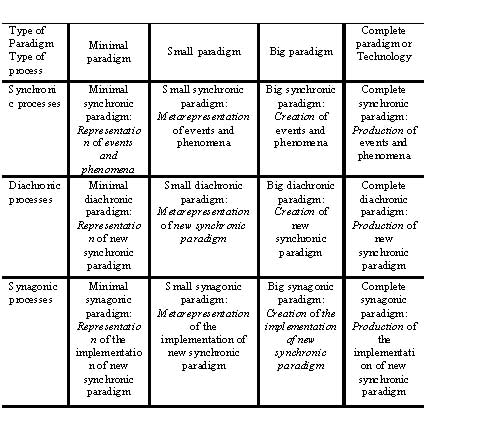

We introduce four types of paradigms: the minimal, the small, the big, and the complete or a technology. It will be shown that meta-representations correspond to small paradigms (see the matrix of paradigmatic archetypes below in the section 2). |

|

Historically, Platonic terminology of ideas includes paradigms, defined as example, archetype, ideal, pattern. Thomas S. Kuhn (Kuhn, 1962) understood paradigms as models of scientific evolution. According to Kuhn, scientific paradigms are neither purely cognitive nor pure social formations. They are matrices of subjects containing: first, symbolic generalizations (e.g. scientific laws); second, ontological models; third, methodical and other valuations; and fourth, examples (e.g., solving of problems). |

|

Concrete examples are used frequently now and are, in fact, identical with the Platonic notion. The most pressing problem of both the Platonic and Kuhn’s construction of the concept of paradigms is that the concept has never been defined with adequate precision. |

|

We, too, understand paradigms as behavioral ideals, as operational norm setting or educating examples of the ur-entity of a paradigm. However, we show that paradigms are not reducible to concepts and therefore demand a separate definition. |

|

Following the intuitive protophysics paradigm of Hugo Dingler and Paul Lorenzen, we construct a paradigm of paradigms and provide arguments for the concept of protosemiotics. |

|

1. Behavior and Paradigms |

|

Semiotics as we understand it deals (interpreting Charles S. Peirce, 1958) with three basic phenomena: sign as the image of a thing or act (mappings), operating with signs as indirect control of operation with things (pragmatics), and the meaning of all of them as a reference to other things or acts (semantics). |

|

Charles W. Morris tried to develop an understanding of signs "on a biological basis and specifically with the framework of the science of behavior" (Morris, 1946). Following Morris’s intention, we develop the full framework of concepts and paradigms as a system of behavioral instruments, used by some intelligent entity and influencing that entity itself. We use the term “sumject”2 to refer to such a cognitively acting entity and its interactions with itself and its world. |

|

Traditionally, most humanist scientists ascribe behavior only to humans and animals. We understand behavior within the tradition of physics. In this sense, behavior means any activity generating a trajectory in an abstract feature-space in which the behavioral entity can be represented with a single point. Such spaces are called Liouville-spaces. Thus, it becomes possible to speak about behavior of things, thoughts, and signs. |

|

It is important to differentiate between “act, operate” and “behave”. Behavior is the most general term. Behavior can be the result of external determination, individual will, or a mix of these. Acting and operation are special cases of behavior involving internal determination or will. |

|

We develop and generalize Thomas S. Kuhn’s initial concept of paradigm as an implicit process of behavioral generation. Based on our generalized paradigms we try to understand all four: sign, operating with signs, phenomena of meaning, and the paradigms themselves. In the following, we omit the word “generalized” when speaking about paradigms in this sense. |

|

We observe that we work with features like green, red, hot, stupid, visionary, cold, big, little, mild, hard, brutal, old, young, existing, not-existing3, here, there, above, under, between, within, inside, outside, single, bounded, restricted, limited, unlimited, open, closed, connected, matched, whole, empty, destroyed, solid, fluid, understandable, known, forgotten, loved, dead, born, yours, hers and so on in every activity. |

|

Analyzing and interpreting our perceptions, we find |

|

• A set of qualities, which are names4 or signs of features; |

|

2 The word “sumject” is a neologism. We built it from Latin “sum” = “I am” and the word |

|

“sum” like “summa”. This construction emphasizes the aspect of generic wholeness. Ger |

|

man: Sumjekt, Russian: суммъект. Depending on the context, sumject can be seen as sub |

|

ject or as object, but it is never reducible to either one. For the definition of sumject and |

|

examples of its use see Schapiro, Schapiro, 2007 and further bibliography there. In gen |

|

eral, we call paradigms the operational deep-processes of the behavior of sumjects. 3 Some features are features only in a specific context. 4 Features are measurable, qualities are not. |

|

• Somebody or something who/which shows behavioral activities. We associate him/it with sumject, observer; • The substance of these activities which we associate with objects; • Difficulty understanding clearly what we are doing, why are we doing it and how good is our activity; • Difficulty understanding clearly what is good, what is will, why and how we want to be good and to do well. |

|

Answers to such questions or explanations of such analyses can not be deduced. We alone are responsible for the answers. |

|

What can we do? We generate special forms of behavior and we decide that these forms of behavior are the answers to our questions. These forms of behavior influence the consequences for us and affect the conditions of our existence. |

|

Considerable experience dealing with such questions and answers forces us to discover the phenomenon of the consequences of our activities. For instance, if we saw off the branch on which we are sitting, we fall down. If we do not use words in proper order, we make a sentence incomprehensible for others. |

|

How we can realize our responsibility for the answers and thus respond to the consequences of our behavior? We create and manage the special behavioral instruments for the realization of our activities. Such instruments are, for instance: decisions, features, comparisons, processes, categories, names, labels, qualities, operators, maps and mapping, concepts, strategies, structures, rules in general and logics in special cases, representations, metarepresentations, paradigms… This list is necessarily incomplete. |

|

These cognitive and mental instruments are intimately interrelated and may not be used arbitrarily. They are neither defined a priori nor can they be deduced. In this sense, they build systems of instruments. The system could be significantly different if one of the instruments operates in different way. |

|

Behavioral instruments – as categories, concepts, features, complexes of features, and paradigms – build systems. Each system of instruments, displays a hierarchy, operating rules, values, and manner of representation, believability rules and more. We interpret the term “representation” in section 2. |

|

Some systems of behavioral instruments seem incompatible with others. Each originates in history and each was proficient in its time and its cultural context. |

|

We must discern between different systems of behavioral instruments. Mental behavior plays especially important role for humans and animals. Mentality (see Schapiro and Schapiro, 1998 for a specific definition) is a special kind of behavior. Mentality is phenomena and forms of self-determination of individuals, groups, and of sumjects in general. The preference for or selection of a particular system of behavioral or mental instruments is a decision. This decision creates the primary context for operating with the recognized phenomena of being. Decisions concerning oneself are basic elements of mentality. |

|

To actualize a decision one must be able to represent it to oneself. One must also be able to evaluate how good a representation inherently is and how useful a representation is for a specific purpose. |

|

2. Paradigms and metarepresentations |

|

Concepts are the consistent feature-complexes of knowledge generated by paradigms. We introduce the concept of paradigm as well as its subspecies as specific feature-complexes of the behavior of sumjects. |

|

We attempt to generalize the gnoseological tool of concepts with the instrument of paradigms in such a way that the new instruments, the paradigms, allow the rational representation of phenomena, particularly in situations where the classical framework of concepts looses its validity. |

|

Paradigms help us recognize the boundaries of concept applicability. Within the valid boundaries of a concept, paradigms should produce equivalent descriptions of the reality of that concept and, in the best case, they should generate corresponding concepts. |

|

We introduce paradigms as deep processes (or implicit processes) of the behavior of observers (of respective sumjects), who generate the respective feature-spaces and act within them. Elements of observer behavior are processes. We also introduce concepts as deep structures (or implicit structures) of observer behavior. We call systems of behavioral instruments paradigms. Paradigms should be able to generate concepts together with their contexts. In general, paradigms generate behavior. |

|

Minimal paradigm: A system of behavioral instruments by which an entity can be differentiated unambiguously from all other things of the world we call the minimal paradigm of this entity. |

|

The minimal paradigm creates representations of entities by differentiating them from all other worldly things, real or imagined. Indeed the minimal paradigm produces not only separations, but also the whole class (= the equivalence class) of separations corresponding to this one entity. This whole equivalence class represents the quality5 of the entity. The minimal paradigm also actualizes a special instrument of observer behavior for providing concepts with names and representing these names as addresses in the feature-space of observer cognition. |

|

Small paradigm: A system of behavioral instruments by which an entity can be differentiated unambiguously from all other things of the world, and ranked within the corresponding class of such entities (their equivalence class) we call the small paradigm of this entity. |

|

The small paradigm does all the minimal paradigm does and then ranks the entity within its equivalence class. |

|

Now we see that if the minimal paradigm generates qualities, then the small paradigm generates features. |

|

Paradigms are entities of the sumject’s behavior. … The exercise of paradigms is possible only through paradigms, because paradigms are not reducible to the concepts of paradigms. |

|

Big paradigm: A system of behavioral instruments by which an entity can be created unambiguously we call the big paradigm of this entity. |

|

Complete paradigm or technology: A system of behavioral instruments by which an entity can be created unambiguously with a priori planned features, we call a complete paradigm or technology of this entity. |

|

Thus, we see four types of paradigms: |

|

• The minimal • The small • The big, and • The complete paradigm or the technology |

|

More about qualities from paradigmatic point of view see in Schapiro, Schapiro, 2007, §1.5. |

|

The complete paradigm is a dependent paradigm. Because the difference between big and complete paradigms is only gradual, we have essentially three independent types of paradigms. |

|

In addition to defining paradigms, we classified processes into three types. It seems that all real processes are one of these three types or either some combination of at least two of these types or some nesting of these types. |

|

There are also three types of processes: |

|

• Synchronic6 (Saussure, 1967): All processes involving one or more entities, seen by an observer within fixed feature-complexes under given cause-and-effect relations, we call synchronic processes. • Diachronic: All processes involving an unpredictable number or kind (especially new kind) of entities, or qualities, or features we call diachronic processes. • Synagonic: All processes of entity integration (also including the absence of an entity) in an existing ensemble of other entities we call synagonic processes.7 |

|

Each process displays the four types of paradigms. However, only three types of paradigms are independent. |

|

Consequently, there are a total of nine in the basic collection of independent types of paradigms (in the central part of the matrix). These nine paradigm archetypes form the complete set of basic generators of behavior. |

|

The difference between big and complete paradigms is gradual. Technology is the extremum of a big paradigm in which the realization of the paradigm’s entity corresponds exactly to the sumject’s intention. |

|

6 The terms “synchronic” and “diachronic” we adopt from Ferdinand de Saussure and use them for generalizing process classification. |

|

7 Synagonic processes, for instance, are technological innovation and reformation of society, administrative tasks and change management. They are the integration of a new child into the old family. They are persuading your colleagues that your new idea is right. They are education and solving of conflicts, peace making and perpetuation of love. They are religious conversion, social rehabilitation after prison or long hospital stay. They are all the things of being or doing together, which create problems but are also extremely important for our everyday life, humanity, and civilization. |

|

Matrix of paradigmatic archetypes

|

|

The matrix of paradigmatic archetypes is in turn the representation of a classification paradigm of paradigms. |

|

All phenomenological perception and action can be generated by combinations, superposition, embedding, complementation, union, recursive procedure, and other operations with the paradigmatic archetypes in the corresponding context of the sumject. |

|

The relation between observable behavior and corresponding paradigm is non-unique. Eventually certain paradigms in different contexts generate the same form of viewed behavior and some paradigm can generate different forms of behavior within different contexts or different sumjects. |

|

3. Paradigms and science |

|

The Cartesian paradigm of science formulates the definition of rationality entirely within the boundaries of logic and strictly separates subject and object. This separation excludes the observer from rational worldview including but not limited by logic of concepts. Several holistic approaches attempted to resolve this dilemma (either human or rational). |

|

The philosophers Hegel and Schelling, the semioticists Peirce and Morris, the biologists Varela and Maturana, the physicists Schroedinger, Prigogine, Eigen, Haken (and this list is far from complete) all developed approaches for resolution. However, their approaches were either inadequately procedural or insufficiently developed or inconsistently evolved, or ideologically predestined to failure. All probably could have benefited from adequate and sufficiently powerful representing instruments like paradigms. |

|

Protophysics (Dingler, 1911; Janich, 1985) is the operational philosophical program for developing the methodical underpinnings of physics. It is operational enough, but excludes observers’ free will and decision-making. |

|

Semiotics researches human and animal competence in dealing with signs. However, also semiotics does not focus on individual decision-making. Semiotics also excludes observer’s free will and individual decision-making. In this sense semiotics is the science. For integration of individual human being, including the free will semiotics also needs its philosophical program for methodical foundation of semiotics. We would call it “Protosemiotics”. |

|

The Theory of Paradigms should contribute to consistent integration of the human being into rational operational research and a holistic worldview. Paradigms are a powerful generalization of concepts and, together with concepts, constitute a new standard of rationality beyond the classical paradigm of science, but excluding occult and esoteric abuse. |

|

In answer to the Bremen workshop’s question, “whether consciousness, (selfconsciousness), art, ideology, science, culture, etc. are meta-representations?” we should say, No, they are not. But meta-representations are necessary for competent action in and with all of them for valuation and judgment of artistic, ideological, scientific, cultural, etc., activities and results. 8 |

|

Authors thank Karl Sittler for his self-sacrificing help in English. |

|

References: |

|

Descartes, R., 1997. Discours de la methode. Franz.-dt., ubers. u. hrsg. v. Luder Gabe, 2. Aufl. Meiner, Hamburg. |

|

Dingler, H., 1911. Die Grundlagen der Angewandten Geometrie. Eine Untersuchung uber den Zusammenhang zwischen Theorie und Erfahrung in den exakten Wissenschaften. Leipzig. |

|

Janich, P., 1985. Protophysics of Time. Constructive Foundation and History of Time Measurement. Series: Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, Vol. 30. |

|

Kuhn, T. S., 1962. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. |

|

Lorenzen, P., 2000. Lehrbuch der konstruktiven Wissenschaftstheorie. J. B. Metzler Verlag, Stuttgart. |

|

Morris, C. W., 1946. Signs, Language and Behavior. Prentice-Hall, New York. |

|

Peirce, C. S., 1958. Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, vols. 1–6, Charles Hartshorne and Paul Weiss (eds.), vols. 7–8, Arthur W. Burks (ed.). Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1931–1935, 1958. Volume 7, Science and Philosophy. |

|

Saussure, de, F., 1967. Grundfragen der allgemeinen Sprachwissenschaft. Walter de Gruyter & Co., Berlin. |

|

Schapiro, B., 1994. An Approach to the Physics of Complexity. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals Vol. 4, No.1, pp.115–123. |

|

Schapiro, B., Schapiro H., 1998. Begriff der Mentalitat und Konzeption des Menschen. Neue Lernverfahren, Ed.: Hans G. Klinzing, DGVT-Verlag, Tuebingen, pp. 41–48. |

|

Schapiro, B., Schapiro, H., 2007. Metarepresentations and Paradigms. Berlin 2007, www.schapiro.org/boris. |

|

Wildgen, W., 2006. Meta-representation and (Self-) Consciousness: Emergence of Higher Levels of Self-organization in Biological and Semiotic Systems. Expose to Bremen workshop, Bremen, 27.–29. of September 2006, University of Bremen, www.arthist.lu.se/kultsem/Ais/sem-bull/c0609bremen.html. |

Шапиро Борис (Барух) Израилевич родился 21 апреля 1944 года в Москве. Окончил физический факультет МГУ (1968). Женившись на немке, эмигрировал (декабрь 1975) в ФРГ, где защитил докторскую диссертацию по физике в Тюбингенском университете (1979). В 1981–1987 годах работал в Регенсбургском университете, занимаясь исследованиями в области теоретической физики и математической динамики языка, затем был начальником теоретического отдела в Институте медицинских и естественно-научных исследований в Ройтлингене, директором координационного штаба по научной и технологической кооперации Германии со странами СНГ.

В 1964–1965 годах создал на физфаке МГУ поэтический семинар «Кленовый лист», участники которого выпускали настенные отчеты в стихах, устраивали чтения, дважды (1964 и 1965) организовали поэтические фестивали, пытались создать поэтический театр. В Регенсбурге стал организатором «Регенсбургских поэтических чтений» (1982–1986) – прошло 29 поэтических представлений с немецкоязычными лириками, переводчиками и литературоведами из Германии, Франции, Австрии и Швейцарии. В 1990 году создал немецкое общество WTK (Wissenschaft-Technologie-Kultur e. V.), которое поддерживает литераторов, художников, устраивает чтения, выставки, публикует поэтические сборники, проводит семинары и конференции, организует научную деятельность (прежде всего для изучения ментальности), деньги на это общество пытается зарабатывать с помощью трансфера технологий из науки в промышленность. Первая книга стихов Шапиро вышла на немецком языке: Metamorphosenkorn (Tubingen, 1981). Его русские стихи опубликованы в сборниках: Соло на флейте (Мюнхен, 1984); то же (СПб.: Петрополь, 1991); Две луны (М.: Ной, 1995), Предрассудок (СПб: Алетейя, 2008); Тринадцать: Поэмы и эссе о поэзии (СПб: Алетейя, 2008), включены в антологию «Освобожденный Улисс».(М.: НЛО, 2004). По оценке Данилы Давыдова, «Борис Шапиро работает на столкновении двух вроде бы сильно расходящихся традиций: лирической пронзительной простоты „парижской ноты“ и лианозовского конкретизма» («Книжное обозрение», 2008, № 12). Шапиро – член Европейского Физического общества (European Physical Society, EPS), Немецкого Физического общества (Deutsche Physikalische Gesellschaft e. V., DPG), Немецкого общества языковедения (Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Sprachwissenschaften e. V., DGfS); Международного ПЕН-клуба, Союза литераторов России (1991). Он отмечен немецкими литературными премиями – фонда искусств Плаас (1984), Международного ПЕН-клуба (1998), Гильдии искусств Германии (1999), фонда К. Аденауэра (2000).