Борис Шапиро

Почему мне не нравится памятник жертвам холокоста в Берлине?

Metarepresentations and Paradigms, Ur-version

WTK - Wissenschaft - Technologie - Kultur e. V. WTK

Experience in Technology Transfer from the CIS Countries to Germany

|

WTK - Wissenschaft - Technologie - Kultur e. V. WTK |

|

|

Experience in Technology Transfer from the CIS Countries to Germany |

|

Boris Schapiro Project Manager, KWTK1 |

|

Translated by Mitch Cohen |

|

WTK Preprint 97-10 Berlin, October 25, 1997 |

|

1 KWTK, Koordinationsstab fur Wissenschaftliche und Technologische Kooperation mit den GUS Landern (Coordination Staff for Scientific and Technological Cooperation with the CIS Countries); Pilot Project of the BMBF (Bundesministerium fur Bildung, Wissenschaft, Forschung und Technologie = German Federal Ministry of Education, Science, Research, and Technology), Sept. 1, 1993 - Sept. 30, 1996, Project 13N 6187 and 13N 6759. |

|

Resume |

|

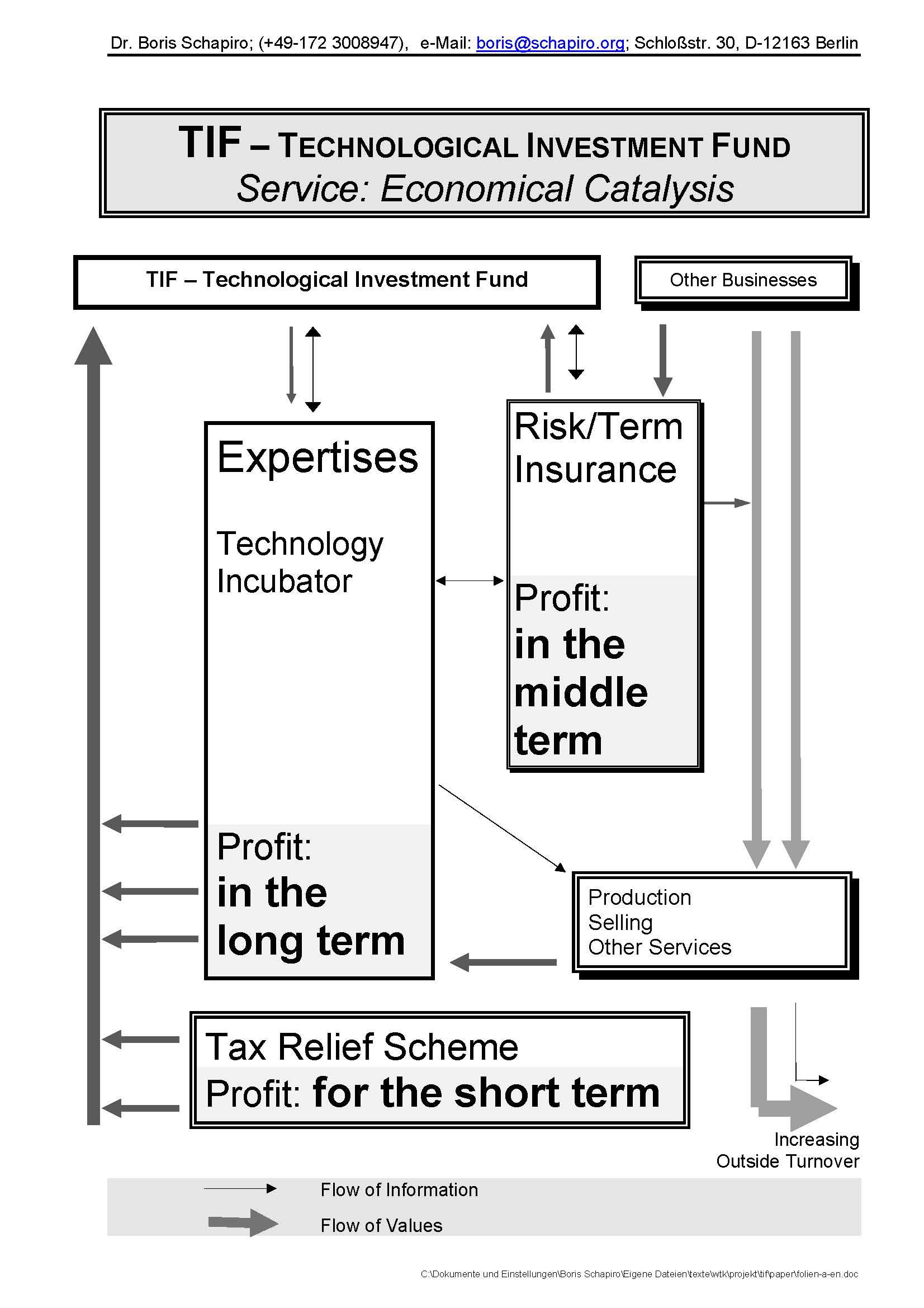

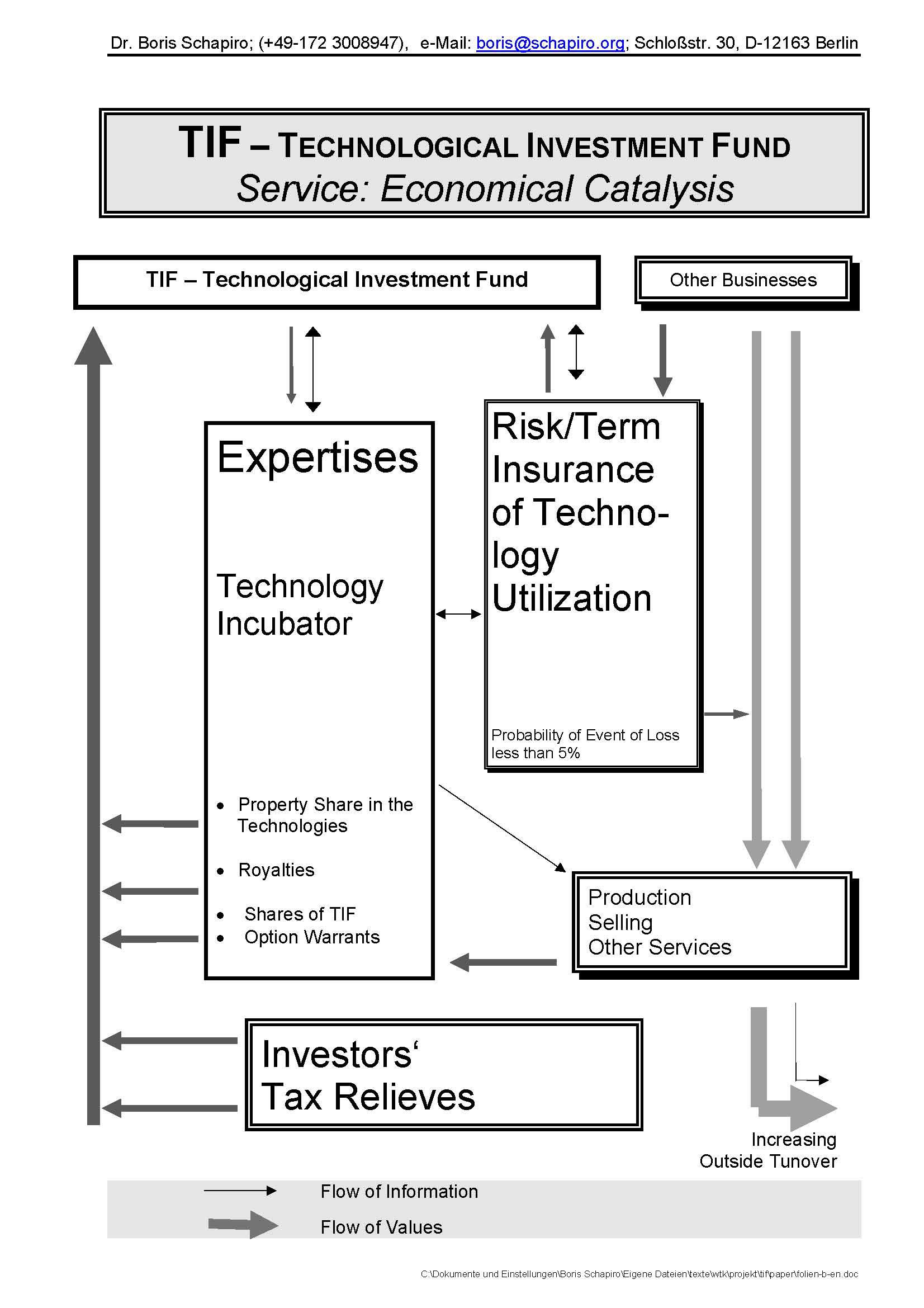

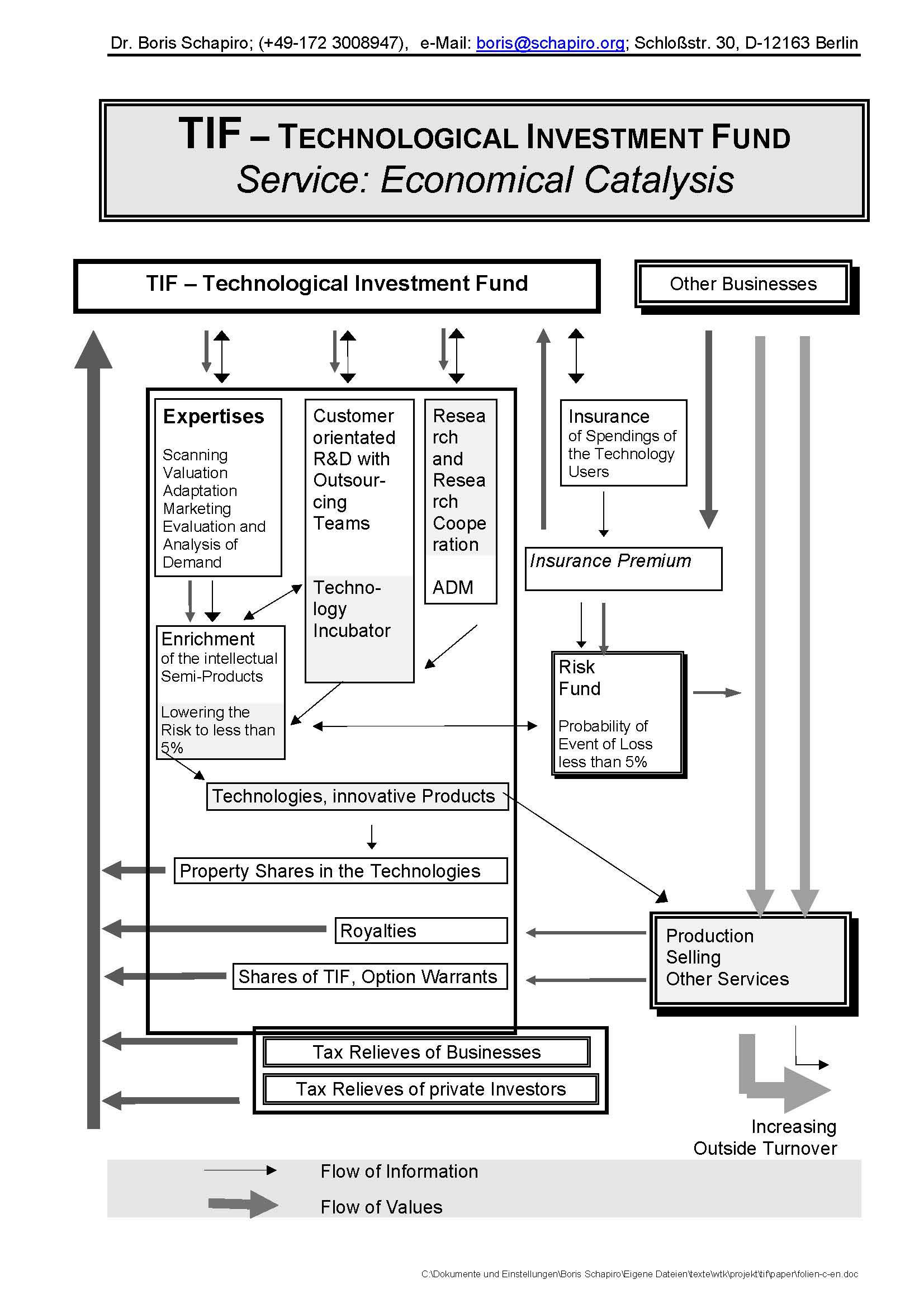

Innovation in the economy or the transfer of knowledge from science and development to production can be systematically, profitably, and thus efficiently advanced only with the aid of a special financial tool. I propose the establishment of a OTechnological Investment FundO as such a tool. |

|

Its primary task would be to make profits by financing the assessment, processing, and marketing of intellectual products, as well as cushioning against failure in the process of innovation. Tax advantages are also important for the Technological Investment Fund’s capital accumulation. They are justified by the beneficial economic effects of the fund’s activity. |

|

This report documents the positive results of a systematic study of the assessment and processing of technological proposals and the assessment of their potential, based on the transfer of technology from the CIS countries to Germany. The proposed Technological Investment Fund is not restricted to Russian technologies, but should act globally. |

|

The study was financed by the BMBF (German Federal Ministry of Education, Science, Research, and Technology) in the framework of the KWTK Pilot Project. |

|

WTK |

|

A. Introduction and Summary |

|

Let us say it once again: over the middle and long term, maintaining Germany at a reasonable level as a site for industry depends substantially on whether and how the problem of innovation in the economy can be solved. While this insight is gradually turning into a neglected cliche, we should at least take a clear look at what other countries are doing in this area. That the research and development potential of the CIS countries and especially of Russia is important and urgent is shown by the corresponding data2 collected on the public and government activities of the U.S.A. |

|

Although this potential is still very large (see Chapter E, Assessment of Potential), it is not endless; and technologies, especially good technologies, are not commodities that stay fresh for long. The German public and especially Germany’s business community must be alerted to the need to increase activity in this direction, so that we too can have access to this significant source of low-priced innovations. Isn’t it time to end the deplorable habit of allowing others to implement ideas originated in Germany -like the fax or Russian-German cooperation in the area of technological innovation -and thus the necessity to pay high prices to benefit from them? |

|

American companies and CIS-US joint venture companies meanwhile have offices in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Nishni Novgorod, Kiev, Minsk, and other CIS cities. Their number and turnover are many times larger than similar German efforts. |

|

With a wide variety of support programs and other activities, the German Research Ministry (BMBF) and Economic Ministry (BWI) support transnational scientific-technological and economic cooperation; the German Chamber of Industry and Commerce (DIHT) has offices in several CIS cities and carries out an enormous amount of work transmitting information, orienting Russian and German companies, coordinating trade and economic cooperation, and representing German business interests in the CIS countries. State ministries promote many innovation initiatives on the basis of regional and supraregional partnership with various republics and administrative units in the CIS countries. The German Defense Ministry has achieved a great deal toward providing housing and economic relief for the Russian army, and thus to promote the economy of sites where the army is stationed in the CIS countries. Banks do what they can to stabilize CIS financing infrastructure. The Arbeitsgemeinschaft fŸr industrienahe Forschung (AiF . Working Group for Industry-Relevant Research) plays an important roll in the promotion of technology transfer, especially for small and medium-sized companies. Germany’s economic giants like Daimler-Benz maintain efficient technology offices. Large and small consulting firms aid in planning and organizing the realization of concrete reform steps and in cultivating contact with and in advising significant decision-makers in the CIS, Germany, and the EU. The press, too, provides enough reliable information on the problems of innovating Germany’s economy and on the pros and cons of cooperation with the CIS. There is no lack of reports on experience or specialized information of all kinds. The German embassy in Moscow actively supports all these efforts and improves the climate for cooperation and mutual understanding. |

|

“Aktivitaten der Regierung und der Offentlichkeit von den Vereinigten Staaten von Amerika in der wissenschaftlich-technologischen Landschaft der GUS und insbesondere im Konversionsbereich des militarisch-wirtschaftlichen Komplexes”, KWTK-report at BMBF (German Federal Ministry of Education, Science, Research, and Technology). |

|

Nonetheless, the economic results of this collective effort are still fairly modest, and sales in the area of innovation remain negligible. What this country lacks to use the existing possibilities for its own and its neighbors’ benefit is a wisely balanced willingness to take risks that would provide a basis for a will to make decisions. |

|

In practice, we have often observed how the demand for maximum security prevents success. The kind of security mentality that grew in the affluent postwar years inhibits economic innovation not only from sources outside of Germany, but also from sources within German science and technology. “Venture capital” and “high-risk investment” remain foreign expressions in German. |

|

Risk assessment is often understood, not as a comparison of possible gains with possible losses, but almost exclusively as a company’s ability to bear the possible losses. The damage to macro-economic development resulting from this systematic avoidance of “trying out” is great, but carries no weight in such “assessments”. |

|

This deplorable habit isn’t caused by bad faith or stupidity, but by the lack of economic instruments and financing infrastructure to bear the evaluation costs and venture financing it requires: the costs for a serious assessment of a business idea are often much higher than to evaluate an applicant’s assets. And even if a proposal is thoroughly evaluated, a certain incalculable risk remains. Certainty can emerge only in practice, since no one is infallible. |

|

Despite the necessity of technological innovation, the costs of an adequately deep evaluation of technological proposals is the real hurdle that reveals the conflict between the micro-economic interests of a company and the macro-economic interests of the state. Both have a clear interest in well-investigated innovation proposals and in successful innovation. But neither can absorb the high assessment costs alone. |

|

A company, especially a small or middle-sized company, might be able to bear the evaluating costs for a single new technology it truly needs, but not for several new technologies. But several have to be assessed to find the right one. An individual company does not have the financial leeway to evaluate several technologies and is unable to find anyone to fund a search for innovations with no certainty of success. |

|

The state is extremely interested in the technological innovation of individual companies, because only the well-being of individual companies can ensure the country’s prosperity. But the state can’t carry the immense costs of massive evaluations either, because (aside from currently empty coffers) technological assessment at public expense would be the equivalent of subsidizing private enterprises, leading to many property and legal problems in the relationship between the state and private companies. |

|

The way out of this conflict was found long ago and is gradually becoming conventional here: the key phrase here is “investment fund”. Based on experience provided by the BMBF pilot project KWTK, I propose the founding of a commercial Technological Investment Fund. |

|

WTK |

|

B. Goal, History, Basic Data |

|

To test new paths of technology transfer from the CIS countries to the Federal Republic of Germany in an efficient and, in the middle term, reasonably priced manner |

|

was the overarching goal of the BMBF pilot project KWTK, the Koordinationsstab fur Wissenschaftliche und Technologische Kooperation mit der GUS (Coordinating Staff for Scientific and Technological Cooperation with the CIS). |

|

On September 1, 1993, after almost two years of preparation, the KWTK was established at the NMI, the Naturwissenschaftliches und Medizinisches Institut (Natural Science and Medical Institute) of the University of Tubingen in Reutlingen. On October 1, 1995, to reduce costs, the project was transferred to the T.I.N.A. Brandenburg GmbH in Potsdam. On September 30, 1996, the BMBF funding ran out, and the KWTK was taken over as a commercial project by the WTK, WissenschaftTechnologie-Kultur e.V. (Association for Science, Technology, and Culture), in Tubingen3. Then the KWTKa was registered as a service trademark at the German patent office. In three years (1993-1996), the KWTK consumed almost 2 million DM (currently the equivalent of about 1 1/8 million dollars) of BMBF funds, a little under 30% of this for expenses in the CIS. |

|

In the end, of 1571 registered filings, 49 proposals have been given priority. 11 of these 49 have already been implemented. I consider another 15 of the 49 implementable in the foreseeable future. Unfortunately, Germany’s major industries are slow in making decisions, even when offered good opportunities. In the four years of its activity, the KWTK transferred technologies and technological services worth about 4.8 million DM (currently the equivalent of about 2.7 million dollars) from the CIS countries to Germany, England, and Sweden. |

|

Noteworthy are the ratios 49:1571 = ca. 3%; 26:49 = ca. 53% (26 = 11 sold + 15 salable). These ratios show that pre-evaluation on site increases the efficiency of implementation by a factor of 17. If the difficulties resulting from financial bottlenecks didn’t have to be overcome, the factor of implementation efficiency would be markedly greater. |

|

C. The KWTK’s Approach |

|

The current approach: step-by-step assessment of technological proposals and comprehensive consulting for creators and owners of technologies from the former Soviet Union, making intensive use of local capacities on a fee basis. |

|

Along with assessing proposals, the KWTK’s consulting activities have proven extremely important from the very beginning. Even proposals originated by renowned and certainly excellent scientists are generally not suited to the usual requirements of German industry, and are thus difficult to assess. |

|

With consultation by freelance partners under the direction of full-time employees, the KWTK’s acceptance procedure helped the designers of innovations to adapt their |

|

3

|

|

Address: WTK e.V., S

|

|

chlo.str. 30, D-12163 Berlin-Steglitz, Germany

|

|

proposals. We have already seen that this gave even the designers themselves a deeper, more precise understanding of their development in the context of the Western market. In this way, the strategy of processing intellectual products from the CIS countries prevailed from the very beginning. |

|

Under the leadership and supervision of 4 (only 3 in 1996) full-time KWTK experts, a contingent of 30 to 60 freelance specialists and other mediators sought new technological approaches and proposals among scientific and technological colleagues working in research and development in the research institutions at the Academy of Sciences, the specialized ministries, the largest development laboratories of the production combines, the R&D facilities of the military-industrial complex, and other suppliers. The German embassy in Moscow and the Moscow delegation from the German Chamber of Industry and Commerce (DIHT) passed on to us many proposals from the former Soviet Union. We received several hundred more offers of cooperation from other CIS exhibitors at trade fairs. The proposals were counted as “filings”. From the mass of filings, our freelance specialists under the leadership of full-time employees reported those proposals deemed worthy of undergoing the KWTK’s assessment procedure. These decisions were made as a result of internal expert opinion in the framework of formal registration. The KWTK counted such filings as registered. The proposals noted for assessment had to be accepted by the KWTK through a special procedure, which generally involved dependent external expert opinion. This expert opinion is termed “dependent” because, during this phase, the external evaluators remained in contact with the originators of the proposals to be assessed, and, under the leadership and supervision of the KWTK’s full-time experts, helped these designers give their proposals the form required by the KWTK. If the dependent external expert opinion came to a positive conclusion, i.e. the acceptance procedure was formally ended, an independent external expert opinion was carried out. Here, the assessor evaluated only the proposal as such. If the independent external expert opinion came to a positive result, the KWTK made a recommendation for the proposed technology and developed a corresponding plan to realize the proposal in German industry. Of course, the KWTK tried to establish useful contacts with interested parties in German industry as early as possible, but not before the technology to be assessed had already shown its potential in the first phases of evaluation. |

|

A significant aspect of our approach strategy was the active evaluation of the need for innovation and direct personal contact with the potential customer. To this end, industry trade fairs are especially important. The KWTK presented its high-priority technologies at the Centerex in 1995 in Vienna, at the Leipzig Innovation Fair in 1995, and at the Hanover Industry Trade Fair in 1996. Participation at the trade fairs was a clear success: five of the technologies sold with our help went to customers won during these trade fairs. |

|

The KWTK’s regular training and informational measures should not be forgotten, either. The KWTK organized trips for Russian specialists to present KWTK plans to German industry and to acquire orders. Each trip by a Russian colleague to |

|

WTK |

|

negotiations, contract-signing, or trade fairs was simultaneously used for educational purposes and to acquire orders. On his trips to Russia, the KWTK’s project manager also held regular (bi-monthly) seminars for the full-time and freelance employees of the KWTK’s Moscow office. These educational measures were in high demand and contributed greatly to the successful processing of intellectual goods. |

|

The tools we developed to register, present, and test the proposals proved to be especially important, as did our contacting originators and owners, as well as the explanatory assistance in filling out our questionnaires. The KWTK’s registration form has been adopted by many Russian R&D facilities and transfer centers, as well as by some Western technology offices. |

|

The proposals given high priority were usually extensively examined for |

|

|

|

+ scientific-technical solidity

|

|

+ adequate economic potential

|

|

+ compatibility with Western production philosophy and development

|

|

strategy + ownership status and other legal considerations

|

|

+ the proposer’s capacity. |

|

Through our assistance or instruction, every technological proposal that was finally presented in negotiations with interested German parties took the form that would give it a real chance in this country. Thus, the KWTK functioned not only as a certifier, but also and substantially as a facilitator. |

|

D. Results: Statistical Overview |

|

When BMBF funding ended, the KWTK had received almost 2,000 cooperation proposals from various sources including: |

|

-research institutes of the Academies of Sciences of Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, |

|

Armenia, Kazakhstan, and Lithuania |

|

-research and development institutes of various Russian specialized ministries |

|

-the Russian State Committee of Science |

|

-research and development institutes of Russia’s military-industrial complex |

|

-various semi-private small and middle-sized development companies |

|

established over the last seven years to market the intellectual products |

|

of the various research institutes. |

|

These cooperation proposals reached the KWTK by several routes. Most came to us via exhibitions and trade fairs or from lists of offerings from corresponding ministries or the Chamber of Industry and Commerce in Moscow. Some were passed on to us by the German embassy in Moscow or the German business delegation in Moscow. We received some proposals through the contact networks our freelancers built up; these proposals generally proved to be the best. |

|

Of a total of almost 2000 filings received, 1571 were finally registered, fed into a specially-developed data bank, and evaluated in accordance with the criteria of technology transfer. Of these, some 200 proposals were completely evaluated. 49 technological proposals turned out to be the most promising. About half of them |

|

appeared actually transferable to the Western industrial context with relatively low post-development costs. 11 of the 49 have already been implemented. |

|

Of special importance is that the KWTK’s consulting activity with owners and suppliers of CIS technologies has transferred (not always the same) 11 of the 49 priority technologies from their original military application to the civilian area. |

|

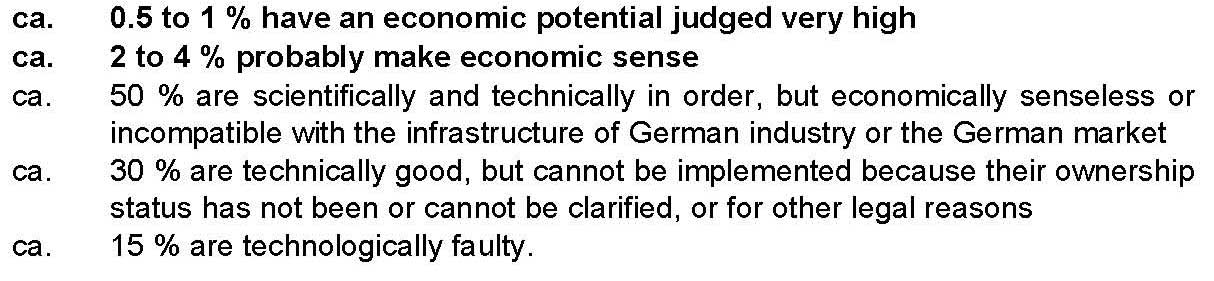

A somewhat more detailed but still qualitative statistic relating to the filings as a whole shows that: |

|

This allows a cautious preliminary judgment of the efficiency of the KWTK’s efforts: |

|

The estimated probability of finding a transferable technological cooperation proposal from the CIS is |

|

without preliminary evaluation about 3 % with on-site preliminary evaluation about 50 %. |

|

The KWTK’s total costs per assessed technology, including all expenses for travel, overhead, personnel, evaluator fees, rent, etc. averaged about DM 1500 per proposal, or about $830 at current exchange rates (total costs divided by the number or pre-evaluated proposals). |

|

At the same depth of evaluation, assessment costs in Germany would be at least 10 to 20 times as high! |

|

It is obvious that, at such a low quota of “bulls eyes”, systematic preliminary evaluation is necessary if one wants to expand technological cooperation systematically. If the preliminary evaluation, choice, and targeted processing of intellectual commodities from the CIS were not carried out on site, their costs would make them unprofitable. But organizing preliminary assessment on site is not easy; it requires special knowhow. |

|

WTK |

|

E. Assessment of Potential |

|

The low quality quota in the technological offerings from the CIS must not mislead one to the conclusion that technological cooperation with the CIS has no serious basis. On the contrary: the absolute number of highly attractive and economically well-founded R&D offerings (with fairly reasonably priced post-development together with the future cooperation partner) is so high that it is definitely worthwhile to look for outstanding achievements on site and to make them usable for industry. |

|

We based our assessment of the potential for transferable innovation on the following: |

|

* the Russian patent office reports that about 300,000 patents and copyrights were issued in the CIS countries over the last 10 years. |

|

* our own research agrees with Russian patent experts’ estimates that in the former Soviet Union only 1/3 of all innovative approaches were registered at the patent office. |

|

1,000,000: We thus dare to assume that, at the present (1995), about 1,000,000 innovative approaches can be found in the CIS countries; 100,000: The KWTK estimate of Soviet science and technology is that about 1/10 |

|

of all these approaches make scientific and technological sense for |

|

industrial application4. |

|

10,000: No fewer than 1/10 of these -about 10,000 -are probably compatible |

|

with Western infrastructures, with the local base of construction |

|

elements, and with our production philosophy. |

|

1,000: 1/10 of these, in turn -about 1,000 -can probably provide enough |

|

economic efficiency or are strategically important enough to justify |

|

transfer and further development. |

|

On the other hand, there are still some 7 million specialists in research and development throughout the territory of the former Soviet Union; of these, 40,000 are habilitated and 300,000 have their doctorate. At many industry research and development facilities, it is not the practice to award academic degrees; thus, the CIS harbors many more highly qualified specialists. |

|

The KWTK’s initial random sample evaluation showed that about 1/30 of Russia’s scientific staff members with doctorates meet the compatibility demands of Western research and development institutions. This assessment corresponds with a potential of 10,000 to 15,000 qualified, productive scientists and technicians who are suited to Western infrastructures. Despite post-Soviet mentality problems, this troop of top specialists can be built up and used in the service of Western industry; this will not come spontaneously, but only after a specialized selection and decentralized registration of potential, so that the compatibility of the technologies with the need for innovation in Germany and other industrial countries can be ensured. This is precisely what the KWTK does. But so far, there has been no continuation or step-by-step expansion to adequately develop Russia’s immense technological potential and to make it usable for German industry – and in the end for Russian industry as well. |

|

This estimate does not contradict the earlier statement that ca. 85% of the registered filings make scientific-technical sense, since several Russian bodies have already examined these technological proposals and offered them for sale. |

|

The two assessment paths stand in qualitatively satisfactory harmony with each other: It seems plausible that ca. 7 million scientists produce 1 million different innovative approaches each year and that 10,000 to 15,000 top Western-oriented specialists possess a few thousand top technologies. |

|

This cautious estimate of the innovation potential for German industry available in the CIS tallies satisfactorily with the extrapolations of the results of our own practice and shows that several thousand truly top technologies with enormous economic potential exist there; but they are obscured by the gigantic number (ca. 1,000,000) of unqualified and occasionally even intentionally misleading proposals. |

|

These top technologies are widely distributed in state and private possession. For security reasons, the originators sometimes even consciously hide them from their own government. Almost all newly developed technologies are in a state precluding their reception by interested Western parties, partly because of the mentality inherited from the Soviet Union, partly because post-Soviet developers are too inexperienced with the requirements of Western standards. |

|

In their existing form and in the time at its disposal, the KWTK was able to address only a small fraction of the existing potential. But this was enough to show that, in contradiction to the view that has developed among some representatives of industry and in Western public opinion, the applicable technological potential of the CIS countries has not even been shown, much less exhausted. |

|

F. The KWTK’s Moscow Office |

|

An important part of the procedural know-how existing in today’s CIS is the creation of a capable, trustworthy, and robust infrastructure. This structure was developed on the basis of the Moscow company Intact Ltd., which represented the KWTK in the CIS as a subcontractor. |

|

At this juncture, the KWTK project manager would like to honor the extraordinarily active, fair, creative, and self-sacrificing behavior of Intact Ltd.’s managers, General Director Vladimir Mulin and Commerce Director Dr. Victor Tjacht, and their staff. |

|

The unusual loss of the purchasing power5 of hard currency in the CIS thrust Intact Ltd. into a position in which it not only made no profit from its subcontract, but actually suffered losses. Nonetheless, Intact Ltd. fulfilled its contract through the end of the BMBF project and compensated the deficits it ran with special skill, iron thrift measures, and individual overwork. |

|

5 We refer here not merely to the inflation of the Rouble in comparison with hard currencies, nor to the latters’ inflation on world financial markets, but to the additional loss of hard currency’s purchasing power in Russia, due to the country’s falling gross domestic product. If commodities are rare enough, they become disproportionately expensive. Cf. Section G4. |

|

WTK |

|

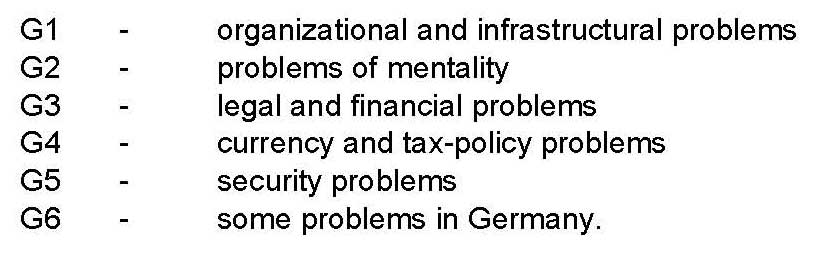

G. Problem Areas |

|

The problems of technology transfer are so complex and varied that the topic demands its own special study. Here, unfortunately, we must make do with an incomplete and superficial sketch: |

|

G1. Organizational and infrastructural problems |

|

It is hardly surprising that there are problems in a country experiencing a phase of upheaval. The greatest imbalance in the CIS is in the relation between authority and responsibility, in managers as well as in technical specialists. Thus, the logistics of decision-making and its organization are more complicated and above all different than in Germany. The ignorance and lack of understanding about this on the part of many interested Western parties often causes their efforts toward economic or technological cooperation in the CIS to fail. |

|

In many cases, taking on-site advantage of evaluating and also consulting assistance allows the KWTK to render decision paths comprehensible and planning possible. People who know the region and its mentality are absolutely necessary. On site, the KWTK’s reputation and weight have not always been enough to solve the logistical problems, especially in clarifying the legal situation and in determining which authorities bear what responsibilities. |

|

Neither Moscow nor the regions have any coordinating office to demand quality certification corresponding to Western requirements from those offering CIS technologies or able to provide them with a certifying service oriented toward transferability. Nor is there anyone yet who could coordinate the cooperation among those offering technologies or who concerns himself with the processing of intellectual products – even though precisely this presents the chance to turn several unsuitable proposals into a few serviceable ones with relatively low investments. |

|

The KWTK does all this to the best of its ability, but of course not across the board or systematically. The achieved synergy has increased the proportion of transferable proposals in our data bank beyond what it would be if we had merely applied selective criteria to existing submissions. This increased the efficiency of the funds employed and markedly increased our prestige among our customers in the CIS. |

|

G2. Problems of Mentality6 |

|

A negative attitude toward market-oriented work is widespread among scientists in Russia. As a result, international efforts to support the reforms in the CIS themselves cause some of the organizational problems. For example, if the ISTC7 program grants support to a request from an R&D institute in the CIS, many developers immediately lose all interest in transfer or the economic application of their topic. The reasons are clear: the result of an ISTC project need be no more than a report and possibly a scientific demonstration with value as scientific knowledge, while for the economically relevant implementation of a development, much more unfamiliar work must be achieved in a rather short time, often accompanied by the loss of (a merely apparent, but familiar) freedom of research. This is just one example of the mental problems hindering international cooperation. |

|

The KWTK has found no antidote yet. This example shows the interplay between problems of organization and of mentality. |

|

Problems of mentality were a substantial part of our difficulties. They were always noticeable whenever a cooperative project ran into difficulties or failed, not due to objective and thus rationally addressable (technical, financial, political, administrative, or pragmatic) limits, but due to irrational (culturally determined, prejudicial, or overemotional) inability to make pragmatic decisions. |

|

The differences between typical German and Russian mentalities become apparent when the basis is lacking for a routine decision. In other words, problems of mentality arise in the area of what is considered a “matter of course”. Where differences in routine and normality are felt, mistrust and aggression arise immediately, on the Russian as well as the German side. |

|

Typical differences in mentality that seem especially prominent from our perspective: |

|

-Many scientists in the CIS have contempt for services as such. |

|

-Rapax8 mentality. The rapax mentality is not exclusively a |

|

Russian phenomenon; in Germany there are also incompatibilities of |

|

mentality between the rapax and the respondens9 types. But the |

|

German society has developed better – though certainly not optimum – |

|

6 The WTK seeks sponsors to support a meeting planned on “Mental Problems of Technology Transfer to Germany from Foreign Countries” for December 1998. |

|

7 ISTC (International Scientific and Technological Center) is a very successful international program whose primary purpose is to promote the maintenance of research potential in the CIS and to reduce the pressure Russian scientists feel to emigrate. |

|

8 The term “rapax” was coined by Janusz Korczak in his last diary to describe the German persecutors in the Warsaw Ghetto in 1942. In the context of our studies of mentality, we generalize Korczak’s term “homo sapiens rapax = predatory rational man” and use it to designate a stereotype of behavior in which decisions are based on a view of mankind and the world in which the decision-maker (whether an individual or a group) is unlimitedly justified in optimizing his choice at the expense of his perceptible surroundings. Thus, the rapax practices a philosophy leading to the irresponsible exploitation of his surroundings. [B. Schapiro, H. Schapiro, contributions to the German-Russian seminar “Problems of Mentality in the Formation of Identity in Conditions of Migration and System Changes”, Oct. 27 -Nov. 11, 1996, Bad Urach; organized by WTK e.V. in cooperation with the Landeszentrale fur Politische Bildung (state center for political education) Baden-Wurttemberg and the Robert Bosch Foundation.] |

|

WTK |

|

structures of protection against the rapax types. The German cooperation partner cannot rely on these mechanisms or their presence in social consciousness in the CIS. |

|

-A sense of responsibility in the Western sense is often lacking. -The proposers often have a false (exaggerated) image of themselves. -Wrong (market-irrelevant) ideas about the kind of cost-benefit |

|

relationship a partner can be expected to accept. -Unfortunately, national arrogance can exist where one doesn’t expect it. |

|

Problems of mentality are not insoluble. And precisely in this area, efforts cost little and produce a great deal. |

|

The KWTK has developed a great number of rational measures in this area. Among |

|

them are -a sober discussion of the problem. -insistence on declaring and clarifying intentions, since intentions are |

|

usually taken as a matter of course and are misunderstood most frequently. |

|

-other trust-building measures. Above all, one should risk extending trust in advance – though not blindly, of course. Here, the risk is almost always smaller than it seems in a specific problematic case. |

|

-both cooperation partners must be informed of their mutual difficulties and fears. |

|

-developing a team spirit. The cooperation partners should understand that they should not approach cooperation as a tug-of-war, but solve their common problem in a comradely fashion. |

|

A basic principle toward solving the conflicts that frequently arise due to lack of trust is mutual information. This is not the place to describe the specific know-how that serves this aim. Informational trips together and, above all, having the Russian partner’s visit Germany promote trust and are effective. |

|

G3. Legal and Financial Problems |

|

All legal problems of technological cooperation have to do with ownership status, just as the financial problems have to do with pricing. |

|

The KWTK places great value on early clarification of the ownership status of the submitted technological proposals and on satisfying all parties involved in their development. We have gathered extensive experience in Russia in evaluating ownership status and in solving the many conflicts over ownership status between |

|

-individual owners (natural persons) -legal persons |

|

We have suggested the term “homo sapiens respondens = responsible rational man” to designate a routine behavior in which decisions are based on a view of mankind and the world in which the decision-maker (whether an individual or a group) is not unlimitedly justified in optimizing his choice at the expense of his perceptible surroundings. Thus, the respondens practices a philosophy in which his responsibility is measured on the basis of optimizing his own well-being together with the well-being of his surroundings. [B. Schapiro, H. Schapiro, contributions to the German-Russian seminar “Problems of Mentality in the Formation of Identity in Conditions of Migration and System Changes”, Oct. 27 -Nov. 11, 1996, Bad Urach; organized by WTK e.V. in cooperation with the Landeszentrale fur Politische Bildung (state center for political education) Baden-Wurttemberg and the Robert Bosch Foundation.] |

|

-laboratories, institute divisions, and institutes -designers and their legal heirs, etc. |

|

Sometimes designers have a hard time understanding that, under Russian as well as German law, they are not the owners of their inventions if they aren’t mentioned in the patent documents, but merely have a certificate that they were the designers. Sometimes clarification of ownership status is complicated by internal political conflicts within institutes. Sometimes it is impossible to clarify or register legal ownership status for an occasional otherwise good development. Issues of national security almost always play a role. |

|

The KWTK accepts a proposal only if the submitter guarantees in writing that it contains no state secrets. |

|

The evaluation and clarification of ownership status was a necessary precondition for registering a technological proposal. |

|

Once the ownership status has been clarified and the technological proposal is well on its way to conversion, problems of legal confidentiality can be solved with an agreement on maintaining commercial and technological secrets. But the KWTK signed two secrecy agreements: one between the KWTK’s Moscow office and the owners within Russian legal jurisdiction, and one between the KWTK in Germany and the owners within German legal jurisdiction. There is no single form that satisfies the Russian side and is valid in both jurisdictions without going through extremely expensive and time-consuming legitimization procedures. |

|

The transfer and storage of confidential information is carried out in accordance with the CIS’s customary secrecy standard Level II. This means that all information considered confidential can be received and passed on in written form only with all pages at issue sewn together, the number of copies noted in writing, and the copies turned over to the evaluators only in exchange for a receipt and for a limited time. After the expert opinion is made, all confidential information is returned to the owner – again, in exchange for a receipt. |

|

A special tangle of problems arises in protecting unpatented intellectual property from the CIS against misuse by potential cooperation partners in Germany. This problem is urgent for the whole field of cooperation between the CIS and the rest of the world. Many technology suppliers in the CIS have had bitter experience with zealous “rip-off artists” from the West, including from Germany. |

|

So far, the KWTK has not found a generally applicable solution to the problem. An easing of the tension it produces can be attributed to the personal skill of our experts. But this problem has also been noted by other facilities involved in the area of technology transfer. It cannot be solved on the level of a single organization, but requires at least a European-wide, perhaps even a worldwide legal reform. |

|

European countries are not alone in their efforts to support the path of reform in the CIS and in their measures to preserve the CIS’s research and development potential. The Russian side complains that support and exchange programs are exporting its scientific potential to other countries at disproportionally low prices. Some authorities in |

|

WTK |

|

the CIS describe the situation as “massive espionage”, “armed robbery”, or even “the plundering of Russia” by the Western victors of the Cold War. |

|

While in our view political slander cannot be justified, it must be admitted that these exaggerated accusations are not fabricated out of thin air, but are based on the CIS’s unmistakable negative experience with some representatives of the West. This is why KWTK assessments take special pains to recognize the realistic market value of the technologies from the CIS, and to convey it and make it plausible to the owners. This not only helps orient the CIS cooperation partners, but also builds trust. Thus, the KWTK contributes to the development of a form of cooperation between the CIS and Germany characterized by fairness and mutual utility. |

|

G4. Currency and Tax-Policy Problems |

|

We are accustomed to thinking of the value of hard currencies, like the US dollar or the German Mark, as being determined by the world market and subject to global, rather than local dynamics. So it was not easy to understand that hard currency follows completely different rules in the CIS. This is due to the continuing fall in production in the CIS. Since the amount of commodities produced in this economic region continues to dwindle and more and more must be imported, less and less value is being created in the country itself. So the price for each unit of commodity in the CIS is rising ever higher in comparison to elsewhere; this is synonymous with a loss of value for hard currency. |

|

From the project’s beginning in September 1993 until the beginning of 1996, the US dollar and, accordingly, the German Mark have dropped in value in the CIS by a factor of about 3.5. Although the total funding volume for the KWTK’s expenses in the CIS was increased in mid-1994 by 120,000 DM from 225,000 DM to 375,000 DM, the value of our budget for our activity in the CIS fell by more than half. (Increase factor 225:120 = 1.875 divided by the reduction factor of ca. 3.5 = ca. 0.54 value loss factor.) This should clearly indicate what financial difficulties and drastic thrift measures the KWTK office had to contend with. |

|

But the regrettable loss of the market value of the Mark does not mean that the KWTK threatens to become more expensive in the CIS countries than the same services would be in Germany. By January 1994, the cost of intellectual labor had fallen by a factor of 13, while the drop in the value of hard currency is already markedly slowing. |

|

In mid-1994, I expected that economic development in the CIS countries and in reunified Germany would stabilize the relationship between the DM and the Rouble at a rate of between 10 and 8. Today, in 1996, intellectual labor in Russia in the least efficient state sector is cheaper than in Germany by a factor of between 8 and 5. In the privatized R&D sector, highly efficient intellectual labor is less expensive than in Germany by a factor of between 2 and 1.5. |

|

Regarding the KWTK’S problems with tax policy, it remains to lament that the KWTK’s outlays in the former Soviet Union are still subject to tax, even though KWTK funds should rightly be seen as aid. Tax payments as high as in the private economy, which further limit the scope of the KWTK’s activities, were another problem. |

|

The Russian tax system changes almost weekly and imposes draconic penalties for infractions or missed deadlines. The KWTK’s efforts to minimize its tax burden were expensive, complicated, and time-consuming. |

|

Increasingly, these currency and tax policy problems making themselves felt in scientific and technological cooperation with the CIS states in general. |

|

G5. Security Problems |

|

The German press has provided much information on security problems in the CIS. Ensuring the necessary security is expensive and time-consuming. |

|

Shortly after 9 in the morning on September 1994, the project manager witnessed a shoot-out on Okjabrskaja Square. He escaped injury only through alertness and much luck. |

|

On December 1994, during a trip in a sleeping car from Moscow to St. Petersburg, the project manager witnessed an attack. When the train was stopped at the Bologoje station, bandits stormed the car, beat up the conductor, and kidnapped from another compartment two passengers they apparently knew. |

|

At the beginning of March 1995, “protection money” extortionists visited the rooms of the KWTK’s Moscow office in the hotel “Ismailowskaja”. To avoid further extortion attempts, we had to evacuate the office overnight and hide. Later we managed to rent new workspace under the roof of the Institute for Space Research (IKI). The hotel “Ismailowskaja” has a well-developed security and surveillance system, but it was still not enough. In 1995, rent at the IKI was 5 times as much as at our office in the hotel. It was still very cheap by Moscow standards and certainly offered adequate security against small-and medium-scale rowdies. But it was still such a burden on the KWTK office’s budget that, if financing continued at the same rate, the money for 1996 would have sufficed for accompanying measures and the completion of those expert opinions already begun, but not to begin new assessments. |

|

Despite all this, the general security situation in Moscow is judged acceptable if adequate security measures are instituted regularly. This is why the use of a vehicle with a trusted driver is indispensible, especially for transports to and from the airport or train station and when one is carrying confidential documents. Crime on streetcars and the subway has markedly fallen recently, though one must still reckon with an occasional attack. In 1996, the danger to the general public due to planned murders of industrialists, bank directors, known journalists, and politicians unfortunately remains on the same level as in recent years – in Moscow, 5 to 8 murders a day. |

|

WTK |

|

G6. Some Problems in Germany. |

|

At this point, we would like to thank the BMBF for its initiative supporting the KWTK project. But coordination work falls smack into the gap yawning between macroeconomic necessity and micro-economic profitability calculations: individual companies, and thus their associations, cannot pre-finance coordination services; the government expects industry to bear the burden of coordination work; and for micro-economic reasons, industry cannot finance such services in the framework of existing economic instruments and infrastructure. |

|

Another problem is the evaluation of the need for innovation. Recognizing the necessity for innovation on the macro-economic level is a far cry from recognizing its necessity in a specific business. Everyday problems and financial bottlenecks are major obstacles to a company’s innovation. Thus, innovation in German companies, especially small-and medium-sized companies, can be fueled only through government measures promoting innovation. |

|

The KWTK is apparently one of the projects with which the BMBF is trying to solve the antinomy sketched above. But the very short funding time kept the KWTK from developing its full effectiveness. Constant uncertainty led to losses, since the threat of the end of the project made reasonable planning for the year impossible and because this uncertainty and falling real salaries limited the colleagues’ motivation. In the three years the project ran, 4 funding requests had to be made (one initial application and 3 extensions). The people involved in the project could not expect reasonable continuity; this greatly limited the KWTK’s overall ability to act. |

|

The KWTK had neither personnel nor funds to research the specific problems of technology transfer in Germany. But our experience made the necessity for such research obvious. |

|

H. Technological Investment Fund |

|

Of course, German business’ notorious weakness in innovation, the “deplorable habit” noted in the introduction, cannot be corrected by a “good talking to”. But aside from a tax reform, neither the laws nor the society must be changed. |

|

What we need to solve Germany’s innovation problem is new, modern financing instruments that flexibly, efficiently, and profitably harness the macro-economic flow of capital to the operating interests of individual companies. One such instrument is already well known: the investment fund. The Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung devotes two or three long essays to the topic of investment funds every Monday.10 |

|

Most of the currently more than 2,700 funds on offer in Germany are from foreign investment companies. In 1997, more than 30 billion Marks11 , or about 17 billion |

|

10 I quote from “Die Zukunft der Investmentbranche hat gerade erst begonnen” (“The Future of the Investment Field has only just Begun”) by F. Zeyer and P. Boer, FAZ, Mon., Oct. 13, 1997, Nr. 237, page 36. |

|

11 In comparison, in 1996, turnover in the arms trade all over the world amounted to ca. 40 billion dollars. |

|

dollars, are expected to flow out of Germany via stock funds alone. The Federal Association of German Investment Companies reports that its somewhat more than sixty members administer a sum of more than a trillion Marks for institutional and private investors. |

|

In Germany, the share of investment funds in the gross domestic product is about ten percent, while the corresponding figure in France, Britain, and the United States exceeds twenty percent. It is hard to overlook the need to catch up and the potential for growth in Germany’s investment fund sector. |

|

In competition for investment capital, better-honed products are available as foreign and domestic technological innovation proposals, which offer a chance at above-average profits. A technological innovation fund with tax advantages could be a hit, especially with the imminent loss of tax advantages for real estate and in the face of ever-diminishing returns on conventional savings products from the credit institutions or on fixed-interest securities. |

|

Compared to the marketing costs for the products or services of many successful investment funds, the initial expenses for the acquisition, evaluation, processing, and follow-up development of the intellectual products of a technological investment fund appear small, while its income from royalties, tax savings, the sale of the fund’s stock, and the newly-established companies, profits, options, etc. should provide a lasting, systematic success in step with the further development of the business and finance system of Germany and Europe. The innovation of the German economy will be the source as well as the consequence of the activity of the technological investment fund, which sees itself as a major catalyst for innovation. |

|

The KWTK’s experience allows a conservative, very rough estimate of Russia’s current economically relevant R&D potential: |

|

=> The ca. 0.5% of the acquirable technologies (more than 1000) corresponds to a |

|

potential of no less than 10 billion US dollars12 . => The other 3% to 5% (ca. 10,000 technologies) corresponds to a potential of no |

|

less than 5 billion US dollars. => The potential for demand-oriented production of new technologies has not been |

|

assessed at all, but must exceed what is known by a great factor. => Of course, we have not considered the macro-economic benefit to Germany, |

|

including additional growth in the value of Germany’s R&D potential through the |

|

utilization of the low-priced Russian potential and the synergetic increase in |

|

value due to the mobilization of capital induced by the structure of the proposed |

|

investment fund. |

|

During the course of the project, we recognized some complex problems and learned to solve them, especially the problem of separating the commercial wheat from the chaff. The KWTK’s very modest sales success should not be judged negatively: it was a BMBF pilot project whose goal, on the one hand, was merely the investigation of possibilities of commercially-oriented technological cooperation with the CIS in principle, and whose budget for this investigation, on the other hand, was less than the |

|

12 All estimates and accounts in the CIS are carried out in the clearing unit customary there, the US dollar. In estimating potential, we have taken into consideration the experience of our American colleagues also involved in technology transfer. |

|

WTK |

|

required “critical mass”. The latter was not an accident or planning mistake, but resulted from the BMBF’s legal obligation as a government body to refrain from interfering with market competition and, consequently, to refrain from directly conducting any business with the taxpayers’ money. |

|

Assuming good operating organization, the median overall costs of the step-by-step evaluation and processing of a technological proposal can be kept to the following level: |

|

ca. 1,000 US dollars to sort out the first 70% |

|

ca. 4,000 US dollars to sort out another 15-20% |

|

ca. 30,000 to 70,000 US dollars to filter out and process the targeted 0.5-3% |

|

from the “processed” remnant of 10-15%. |

|

These estimates assume the use of improved tools and all of our know-how in the initial selection of technological proposals for evaluation. All technologies – including the best from the CIS and most of those from German science – have to be adjusted to the needs of production and the markets. This can be done most efficiently in cooperation with the potential buyers and the aid of risk financing from the technological investment fund. |

|

On the basis of the experience presented here, made possible by the BMBF pilot project KWTK, I propose the founding of a technological investment fund for the intensive evaluation, follow-up development, and exploitation of intellectual products from CIS science and technology. |

|

The logic of the matter itself should be enough to interest companies, consultants, bank, business, and financing associations, governments, governmental bodies, R&D, research, and educational facilities, as well as institutional and private investors in the establishment of such an economic instrument, which can solve problems and conflicts of interest between various structural levels – macro-economic / individual company / science and technology – in a manner effective and profitable for all involved. |

|

Over the long term, the innovation of small and medium-sized companies, which add up to a great mass, can be carried out only on the basis of risk financing, i.e. through an investment fund. But large companies, too, can only profit from a technological investment fund. |

|

The fact is, the R&D potential and the intellectual services of the CIS are being utilized by American, Korean, Canadian, French, British, Japanese, Swedish, Chinese, and other companies with increasing profit, while German companies’ utilization is negligible. |

|

We see this, because during the evaluation of more than one-and-a-half thousand technological proposals, we built up contact and trust with several thousand experts and representatives of owners, and because some of the technologies we processed were sold to these foreign investors, due to decision-times unacceptable to the owners and, finally, due to the lack of risk financing in Germany. This usually occurred without our doing, but we were almost always told why this or that technology was no longer available: in the framework of the pilot project, we had no financial ability to conclude binding contracts with the owners. |

|

For years, private and government facilities in Germany, Europe, and all over the world have striven to promote and open up the R&D potential of the former Soviet Union. German ministries’ cooperation plans; efforts by the Steinbeisstiftung; the experience of the DIHT, Siemens, Daimler Benz, IBM, INTEL, Microsoft, Perkin Elmer, and General Motors; the patronage of G. Soros; EU support programs like INTAS, PHARE, TACIS; and many other politically or pragmatically motivated activities have prepared the ground in the CIS and developed competence in the West to find a commercially successful solution to the problem of economic innovation in Germany and Europe and simultaneously to preserve the R&D potential of the former Soviet Union. The means toward this end is a technological investment fund. |

|

The technological investment fund must not restrict itself to Russian technology. This is only one, the currently best-investigated example; the proven potential of the CIS must convince. Exploiting it, however, requires special know-how – as in any other region. The profit-oriented service of the technological investment fund should operate worldwide in scanning, evaluating, and processing intellectual products and services from science and development, as well as in marketing to business and in insuring against the failure of evaluated innovation proposals. |

|

I. Acknowledgments |

|

Once again, I would like to thank the BMBF, in the persons of Dr. Kramers and Dr. Bandels, for their understanding of the complex of problems, and the ministry for its financial support for the pilot project. |

|

I also owe gratitude to the VDI (Verein Deutsche Ingenieure – Association of German Engineers), the project carriers, especially Dr. Leson, who never ceased providing the project with constructive suggestions and help. I also thank Ms. Steinhof for her economic-administrative assistance. |

|

Special thanks are due to the managers of the Intact company, General Director Vladimir Mulin and Commerce Director Dr. Victor Tjacht, and to their employees. |

|

I cordially thank the NMI, the Natural Scientific and Medical Institute at the University of Tubingen in Reutlingen, in whose framework the KWTK pilot project arose, in the person of Director Dr. Enzio Muller and his deputy, Dr. Otto Inacker, as well my dear colleagues, for their support and the wonderful atmosphere during our years working together. |

|

Most cordially of all, I thank the NMI’s former Director, Dr. Gunter Hoff. Without his active support and visionary encouragement, the KWTK project would never have been born. |

Шапиро Борис (Барух) Израилевич родился 21 апреля 1944 года в Москве. Окончил физический факультет МГУ (1968). Женившись на немке, эмигрировал (декабрь 1975) в ФРГ, где защитил докторскую диссертацию по физике в Тюбингенском университете (1979). В 1981–1987 годах работал в Регенсбургском университете, занимаясь исследованиями в области теоретической физики и математической динамики языка, затем был начальником теоретического отдела в Институте медицинских и естественно-научных исследований в Ройтлингене, директором координационного штаба по научной и технологической кооперации Германии со странами СНГ.

В 1964–1965 годах создал на физфаке МГУ поэтический семинар «Кленовый лист», участники которого выпускали настенные отчеты в стихах, устраивали чтения, дважды (1964 и 1965) организовали поэтические фестивали, пытались создать поэтический театр. В Регенсбурге стал организатором «Регенсбургских поэтических чтений» (1982–1986) – прошло 29 поэтических представлений с немецкоязычными лириками, переводчиками и литературоведами из Германии, Франции, Австрии и Швейцарии. В 1990 году создал немецкое общество WTK (Wissenschaft-Technologie-Kultur e. V.), которое поддерживает литераторов, художников, устраивает чтения, выставки, публикует поэтические сборники, проводит семинары и конференции, организует научную деятельность (прежде всего для изучения ментальности), деньги на это общество пытается зарабатывать с помощью трансфера технологий из науки в промышленность. Первая книга стихов Шапиро вышла на немецком языке: Metamorphosenkorn (Tubingen, 1981). Его русские стихи опубликованы в сборниках: Соло на флейте (Мюнхен, 1984); то же (СПб.: Петрополь, 1991); Две луны (М.: Ной, 1995), Предрассудок (СПб: Алетейя, 2008); Тринадцать: Поэмы и эссе о поэзии (СПб: Алетейя, 2008), включены в антологию «Освобожденный Улисс».(М.: НЛО, 2004). По оценке Данилы Давыдова, «Борис Шапиро работает на столкновении двух вроде бы сильно расходящихся традиций: лирической пронзительной простоты „парижской ноты“ и лианозовского конкретизма» («Книжное обозрение», 2008, № 12). Шапиро – член Европейского Физического общества (European Physical Society, EPS), Немецкого Физического общества (Deutsche Physikalische Gesellschaft e. V., DPG), Немецкого общества языковедения (Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Sprachwissenschaften e. V., DGfS); Международного ПЕН-клуба, Союза литераторов России (1991). Он отмечен немецкими литературными премиями – фонда искусств Плаас (1984), Международного ПЕН-клуба (1998), Гильдии искусств Германии (1999), фонда К. Аденауэра (2000).